Why We Still Love the Zapatistas

چرا ما هنوز عاشق زاپاتیست ها هستیم

INSPIRATION FROM CHIAPAS

The construction of a new world is much more than an academic exercise.

ساختن یک دنیای جدید خیلی بیشتر از یک تمرین آکادمیک هست.

ترجمه از : پیمان پایدار

- Issue #0

- AUTHOR

- Leonidas Oikonomakis

- لئونیداس اویکونوماکیس

- دسامبر 2015

Primero de enero 1994. 3:00am.

The Mexican President Carlos Salinas de Gortari has gone to bed happy that towards the end of his mandate Mexico joins the North American Free Trade Agreement, or NAFTA. Goods, capital and services will now move freely between Mexico, Canada, and the United States of America. Of course the agreement mentions nothing about the border wall between Mexico and the US. Free movement of goods, capital, and services, we said—not of people.

At the same time, the removal of trade protectionist measures practically opens up the Mexican economy to Canadian and American goods that are produced more cheaply and in greater quantities (in some cases even genetically modified). Bad news for the Mexican farmers, that is, who also find a “for sale” sign hanging on their ejidos—the communal land which had until then been protected from privatization by the Mexican Constitution.

اول ژانویه 1994:ساعت3 صبح

رئیس جمهور مکزیک کارلوس سالیناس ده گورتاری خوشحال به رختخواب رفت واسه اینکه در پایان دولتش به توافقنامه تجارت آزاد آمریکای شمالی پیوست، یا نفتا (مخفف مذکور-م). حالا محصولات، سرمایه و خدمات آزادانه بین مکزیک، کانادا، و ایالات متحده آمریکا در رفت و آمد خواهد بود. البته توافق هیچ ذکری در مورد دیوار بین مرز مکزیک و ایالات متحده نمیکند. ما از حرکت آزاد کالا، سرمایه و خدمات گفتیم، نه از مردم .

هم زمان، حذف اقدامات حمایتی تجاری عملا اقتصاد مکزیک را به ورود محصولات کانادا و آمریکا که ارزان تر و به مقادیر بیشتری تولید میشود باز میکند (در برخی موارد حتی محصولات ژنتیکی اصلاح شده). خبر بد برای کشاورزان مکزیکی، این بود که ، آنها علامت "برای فروش" را بر سردر زمینهای جمعی شان -که تا آن زمان از خصوصی سازی در قانون اساسی مکزیک محافظت شده بوده- می یابند.

The government propaganda machine, however, can “sell” the agreement with plenty of fanfare, praising the president for this “triumph”: Mexico is finally joining the First World!

Riiiing, riiiing, riiiing!!!!!!

The man who awoke Carlos Salinas from his “First World dreams” was his secretary of defense, General Antonio Riviello Bazán, who announced that there had just been a rebellion in Chiapas. Thousands of masked armed men and women had occupied several cities of the southeastern Mexican state. They were calling themselves Zapatistas, and their army the EZLN.

دستگاه تبلیغاتی دولت، با این حال، می تواند موافقتنامه را با چاشنی زیادی از هیاهو و جارو جنجال "بخورد" مردم دهد، ستایش کند از رئيس جمهور برای این "پیروزی": مکزیک بالاخره به جهان اول پیوست!

رینگ، رینگ،(صدای تلفن) رینگ

رینگ، رینگ،(صدای تلفن) رینگ

مردی که کارلوس سالیناس را از "رویاهای جهان اول" بیدار کرد وزیر دفاع بود، ژنرال آنتونیو ریویه یو بازان، که اعلام کرد که شورشی در چیاپاس بوقوع پیوسته. هزاران نفر از مردان و زنان مسلح نقاب دار چندین شهررا در جنوب شرقی مکزیک اشغال کرده اند. آنها خود را زاپاتیستها و ارتششان را 'ارتش رهائیبخش ملی زاپاتیستا' مینامند .

“APOLOGIES FOR THE INCONVENIENCE BUT THIS IS A REVOLUTION!”

"عذر خواهی برای ناراحتی اما این یک انقلاب است!"

For Mexico, Latin America and the international left, what emerged from the Chiapan mist along with the Zapatistas was the specter of revolution with a capital R—something the Mexican autocracy of the ruling Partido Revolucionario Institucional, the PRI, believed it had killed a long time ago, in the late 1970s.

برای مکزیک، آمریکای لاتین و چپ بین

الملل، چیزی که ازغبارچیاپاس همراه با زاپاتیستها ظهورکرد شبح انقلاب بود با الف بزرگ(آر به انگلیسی-م) - چیزی که استبداد حاکم "حزب نهادینه انقلابی"/ پی آر آی(نام بی مسمای حزب ارتجاعی حاکم ، که پس از انقلاب پرشکوه ولی شکست خورده مکزیک،حدودا همزمان با انقلاب شکست خورده مشروطه ایران،بمدت هفتاد سال برمکزیک حکومت کرده)، معتقد بود مدتها پیش آنرا نابود کرده بوده ، در اواخر 1970.

What emerged from the Chiapan mist along with the Zapatistas was the specter of revolution with a capital R.

Ever since the Tlatelolco massacre of 1968, a few days before the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games in Mexico City, Mexico’s youth had stopped believing in the possibility of social change through protests and elections. Some of them influenced by the Cuban revolution, others by Maoist thought and praxis, they took to the mountains and the cities of the country with the idea of organizing a rebel army that would overthrow the PRI government and bring socialism to Mexico. According to Laura Castellanos, in her book México Armado, more than 30 urban and rural guerrilla groups were active in the country between 1960 and 1980.

از زمان قتل عام تلاتلولکو(کشتن حدود 300 دانشجو رادیکال و دستگیری 1500 نفر دیگر در میدان 'سه فرهنگ'-م) در سال 1968، چند روز(ده روز-م) قبل از مراسم افتتاحیه بازی های المپیک در شهر مکزیکو، جوانان مکزیکی اعتقادشان را به امکان تغییر اجتماعی از طریق تظاهرات و انتخابات از دست داده بودند. برخی از آنها متاثر از انقلاب کوبا،برخی دیگر با تاثیراز اندیشه و پراکسس (عمل) مائوتسه تنگ ، به کوه ها و شهرهای کشور رفتند تا با ایده سازماندهی یک ارتش شورشی به سرنگونی حزب حاکم دولت و برقراری سوسیالیسم در مکزیک بپردازند. بزعم 'لاورا کسته ینوس'، در کتابش بنام مکزیک مسلح ، بیش از 30 گروه چریک شهری و روستایی بین سال های 1960 و1980 در کشور فعال بودند .

The Mexican state launched a war against its youth, who were killed, tortured and disappeared systematically in a dark period that became known as la guerra sucia: the dirty war. Thousands are still missing, others were found dead in mass graves, and thousands more were tortured and imprisoned in military barracks. With the amnesty and the new electoral law of 1978 the government thought it was done with the revolutionaries, with their foquismo and their prolonged people’s wars.

Well… not with all of them!

دولت مکزیک جنگی را علیه جوانان خود براه انداخت، که کشته، شکنجه و بگونه سیستماتیک در یک دوره تاریکی ناپدید کشتند و آن بعنوان ''گرا سوسیا' شناخته شده:جنگ کثیف. هزاران نفر هنوز مفقود هستند، عده ای دیگر مرده در گورهای دسته جمعی پیدا شدند، و هزاران نفر دیگر شکنجه و در پادگانهای نظامی زندانی شدند. با عفو و قانون انتخابات جدید 1978 دولت فکر کرد دخل انقلابیون را آورده، با تئوری ' فوکو'شان(اقتباس از کتاب 'رژی دبره' متاثر از چه گوارا که رفقای چریک فدائی خلق نیز در سالهای 1349-1346 در ایران به تدارک جنگ چریکی رفتند-م) و جنگ طولانی مدت مردمی.خب...نه همشون را!

LAS FUERZAS AND ZAPATISMO

نیروها و زاپاتیسم

One of those guerrillas of the late 1960s and early 1970s was a group called the Fuerzas de Liberación Nacional, or FLN. It was neither the most well known nor the best organized, and it never attracted large numbers of recruits. The FLN was, in fact, a very otherly guerrilla group. It never engaged in bank robberies, kidnappings or other spectacular actions to make a name for itself, as was customary among revolutionary groups at the time.

یکی از این گروههای چریکی اواخر 1960 واوایل 1970 گروهی به نام نیروهای آزادی بخش ملی، و یا اف ال ان بود. نه از شناخته شده ترین و نه بهترین در سازمان یافتگی، و آنها هرگز تعداد زیادی از نیروها را بخود جلب نکردند. نیروهای آزادیبخش ملی، در واقع، یک گروه چریکی متفاوتی بود . آنها هرگز در سرقت از بانک، آدم ربایی یا سایر اقدامات چشمگیر درگیرنبودند تا نامی برای خود بسازند،چیزی که در میان گروه های انقلابی در آن زمان مرسوم بود.

Perhaps it was their strategy of staying and acting underground that allowed them to survive at a time when other groups were being uprooted by the state—even though they themselves also came close to extinction more than once, with the most exemplary cases being the discovery of their main safe house in Nepantla and the assassination of most of their leading cadres in their training camp in Chiapas, near Ocosingo, in 1974.

شاید استراتژی زیر زمینی ماندن و اقدام زیر زمینی کردن به آنها اجازه زنده ماندن در زمانی را داد که گروه های دیگر توسط دولت ریشه کن شدند - هر چند آنها نیز خود بیش از یکبار نزدیک به انقراض بودند، نمونه مورد خاصش همانا کشف خانه اصلی امنی شان درنپانتلا و ترور اکثریت کادرهای اصلی آن در اردوگاه آموزشی خود در چیاپاس، در نزدیکی اوکوسینگو، در سال 1974.

However, through painful trial and dramatic error, the FLN managed to not disband like most other groups. They rejected the Amnesty of 1978 and finally installed a rebel army in Chiapas in 1983; an army that would be embraced by the indigenous Tsotsiles, Tseltales, Choles, Tojolabales, Zoques and Mames of the region during the 1980s, and that would take Mexico and the world by surprise on January 1, 1994. That army was the EZLN.

با این حال، از طریق آزمون دردناک و اشتباهی ترسناک ، نیروهای آزادیبخش ملی موفق شدند که به مانند دیگر گروهها منحل نشوند. آنها عفو 1978 را رد کردند و در نهایت در سال 1983 دست به تشکیل یک ارتش شورشی در چیاپاس زدند؛ ارتشی که با آغوش باز بومی هائی منطقه چون سوتسیلز،سلتالز، چولز،توخلابالس ، زوکس و مامس در طول دهه 1980 روبرو گردید، که مکزیک و جهان را در اول ژانویه، 1994شگفت زده کرد. آن ارتش ملی آزادیبخش زاپاتیستا بود.

چیزی که به عنوان شاخه مسلح یک سازمان پیشتاز و شدیدا سلسله مراتبی شروع شده بود به زودی نظریه هایش توسط واقعیت بومی و اراده مردمی که آمده بودند برایشان "روشنگری کنند" خرد گردید.What began as the armed branch of a vanguardist and strictly hierarchical organization soon found its theories crushed by the indigenous reality and the will of the people they had come to

“enlighten.”

Of course, in the period leading up to the uprising of 1994, the EZLN had also become very otherly.

البته، در دوره منتهی به شورش/قیام سال 1994،ارتش ملی آزادیبخش زاپاتیستا خود همچنین بسیار تحول یافت.

البته، در دوره منتهی به شورش/قیام سال 1994،ارتش ملی آزادیبخش زاپاتیستا خود همچنین بسیار تحول یافت.

What began as the armed branch of a Castro-Guevarist, vanguardist and strictly hierarchical organization soon found its theories crushed by the indigenous reality and the will of the people they had come to “enlighten” deep in the mountains and jungles of the Mexican southeast. The vanguardism of the FLN was at odds with the assemblyist customs of the indigenous populations of Chiapas, which also owed in part to relevant previous work done in the region by liberation theologists and Maoist militants.

چیزی که به عنوان شاخه مسلح یک سازمان کاسترو-چه گواراریسم، پیشتاز و به شدت سلسله مراتبی شروع شده بود به زودی نظریه هایش زیر بار واقعیت بومی و اراده مردم اعماق کوه ها و جنگل های جنوب شرقی مکزیک که آمده بودند برایشان"روشنگری کنند" خرد گردید. تفکر پیشتاز نیروهای ملی آزادیبخش در تقابل بود با آداب و رسوم انجمن گرایانه جمعیت بومی چیاپاس، که همچنین بخشا ارتباط داشت و متاثر گردیده بود از فعالیتهای صورت گرفته شده قبلی توسط جنبش 'الهیات آزادیبخش'(برداشت 'انقلابی' از انجیل که بنیانگذارش گوستاوو گوتیرز* پروئی میباشد-م) و مبارزین مائوئیست .

Soon the EZLN realized that if it was to be successful it would have to change. It chose to break with its outmoded vanguardism and adopted a more assemblyist organizational form and decision-making structure. Years later, it would set off to “march all the way to Mexico City,” as the First Declaration of the Lacandona Jungle put it.

به زودی ارتش ملی آزادیبخش زاپاتیستا متوجه شد که اگر میخواهند موفق شوند میبایست تغییر کنند. تصمیم به قطع رابطه با شیوه پیشتازگرایانه کهنه/دموده شده کرده و اتخاذ به شیوه سازماندهی انجمن گرایانه و ساختار تصمیم گیرانه گرفتند. سالها بعد، دست به "راهپیمایی به سمت مکزیکو سیتی،"، آنطور که اولین اعلامیه از جنگل لاکندونا میگوید ، زدند .

However, things did not really turn out exactly as the Zapatistas had expected them to. Their call to arms was not answered by the Mexican people, who—instead of taking to the mountains—took to the streets to demand peace and to stop the Mexican army from exterminating the EZLN.

با این حال، همه چیز واقعا آنطوری که زاپاتیستا انتظارش را داشتند رخ نداد. خواست آنها برای اسلحه بدست گرفتن توسط مردم مکزیک پاسخ در خور توجه ای نگرفت، که- به جای رفتن به کوهستانها -به خیابان ها ریختند و خواستار صلح شده و اینکه جلوگیری کنند از نابودی زاپاتیستا توسط ارتش مکزیک.

Peace negotiations followed and the San Andrés Accords were signed, practically granting autonomy to the EZLN institutionally, only for the agreement to be abruptly dishonored by the government. After this, the EZLN announced that they would continue down the road of autonomy—de facto and not de jure this time—and that is exactly what they have been working on ever since: creating new pathways and opening up new horizons of the imagination far beyond the impasses of the traditional left.

مذاکرات صلح به دنبال خود امضای پیمان سن آندرز را بدنبال داشت، بخصوص اعطای خودمختاری نهادینه به زاپاتیستا،در حالی که بطور ناگهانیتوسط دولت نقض شد. بعد از این،زاپاتیستا اعلام کردند که آنها در راستای راه خودمختاری خود ادامه خواهند داد-اینبارعملا و نه به لحاظ قانونی- و این دقیقا همان چیزی که آنها تا کنون مشغول به کار بوده اند: ایجاد مسیرهای جدید و باز کردن افق های جدید از تخیل فراتراز بن بستهای چپ سنتی.

CRITICISM FROM THE LEFT

نقد چپی ها

As a result of their otherly strategies—and thanks, of course, to the sharp pen of Subcomandante Marcos (now renamed Galeano)—the Zapatistas became an emblematic reference point for the international left, and a visit to Chiapas and the intercontinental encuentros of the EZLN became a necessary pilgrimage for activists in the alter-globalization movement. However, especially in recent years, the Zapatistas have also become the target of criticism from those on the more traditional and institutional left.

Take, for instance, a recent article by Bhaskar Sunkara, in which the editor and publisher of Jacobin depicts the Zapatistas as a sympathetic but rather unfortunate role model for the international left.

برای مثال، مقاله اخیر باسکار سونکارا، که در آن سردبیر و ناشر ژاکوبین زاپاتیستا را به عنوان یک الگوی دلسوز/ سمپات می انگارد اما بعنوان الگو آنها را مایه تاسف برای چپ بین الملل میداند.

Apart from the obvious errors of his piece, apparently the result of limited familiarity with the case (the FLN were not Maoist and did not vanish “as quickly as they had appeared,” but rather lasted longer than any other guerrilla group of their time; Subcomandante Marcos was not amongst the founding members of the EZLN’s first camp in 1983 but rather took to the mountains a year later), Sunkara’s is an effort to discredit the Zapatistas on ideological terms, mainly because—in his view—they became the inspirational reference point for movements that simply negate and do not create.

به غیر از خطاهای آشکار این نوشته ، ظاهرا نتیجه آشنایی محدود با این مورد (نیروی آزادیبخش ملی مائویست نبود و ناپدید نشد "بهمان سرعتی که ظاهر شدند،" بلکه بیش از هر گروه چریکی دیگردر زمان خود دوام آوردند; مارکوس در میان اعضای موسس اردوگاه اول زاپاتیستا در سال 1983 نبود بلکه یکسال بعد به کوه زد)، نوشته سونکارا به منظور بی اعتبار ساختن زاپاتیستا از لحاظ ایدئولوژیک میباشد ،عمدتا به این دلیل که- از نظر او- آنها منبع الهام بخشی برای جنبشهائی شدند که به سادگی نفی میکند و دست به ساختن نمی زنند .

Sunkara also argues that the influence of the Zapatistas is unjustified as Chiapas actually remains a deeply impoverished region “without much to show for almost two decades of revolution.” In Sunkara’s view, representative to some extent of the old left, we loved the Zapatistas because we were “afraid of political power and political decisions.” And he argues that the Zapatistas—and those inspired by them—did not achieve much. The only meaningful way forward, it seems, is an organized working-class movement in the Marxist-Leninist tradition.

سونکارا همچنین استدلال می کند که نفوذ زاپاتیست ناموجه است چرا که چیاپاس در واقع یک منطقه عمیقا فقیر باقی مانده است "بدون اینکه چیزی را بتوانند بعد از تقریبا دو دهه از انقلاب نشان دهند." به نظر سونکارا، تا حدی نماینده چپ قدیمی، ما عاشق زاپاتیست شدیم چون ما "از قدرت سیاسی و تصمیم گیری های سیاسی ترس داشتیم ." و او میگوید که زاپاتیستا-و کسانی که از آنها الهام گرفتند- چیز زیادی بدست نیاوردند. تنها راه معنی دار رو به جلو، به نظر می رسد، یک جنبش سازمان یافته طبقه کارگر در سنت مارکسیستی-لنینیستی است.WITHOUT MUCH TO SHOW FOR?

بدون اینکه چیز زیادی برای برخ کشیدن داشته باشند؟

In defense of his argument, Sunkara offers some statistical data on Chiapas illustrating that the region has not changed much in the past 20 years: illiteracy still stands at over 20 percent, running water, electricity, and sewage are still non-existent in many communities, and infant mortality rates are still extremely high.

در دفاع از استدلال خود، سونکارا برخی داده های آماری را در مورد چیاپاس ارائه داده و نشان می دهد که منطقه در 20 سال گذشته تغییر زیادی نکرده است: بی سوادی هنوز بیش از 20 درصد است، آب، برق، و فاضلاب هنوزدر بسیاری از کومونیته ها موجود نمیباشد ، و نرخ مرگ و میر نوزادان هنوز خیلی بالاست.

These statistics are correct—but statistics do not always tell the whole truth.

این آمار صحیح میباشند-اما آمار همیشه تمام حقیقت را نمی گویند.

If Sunkara had actually researched his case a little better, he would have found out that his statistics, which are presumably derived from the Mexican state’s National Statistical Agency (the source is not mentioned in the article), mainly refer to the non-Zapatista communities. Chiapas is an enormous region, roughly as big as Ireland, and out of the 5 million people who inhabit it, between 200.000 and 300.000 are actually Zapatistas.

Furthermore, most of the Zapatista communities, the so-called bases de apoyo, are not depicted in any official data since they do not allow access to state authorities: they are autonomous. And while Sunkara is right in that social transformation “can be examined empirically,” his article—relying on a narrowly developmentalist logic of statistical change—fails to do precisely that.

علاوه بر این، بسیاری از کومونیته های زاپاتیستا، به اصطلاح پایگاه های حمایتی، در اطلاعات رسمی به تصویر کشیده نمی شوند از آنجایی که آنها اجازه دسترسی به -مقامات دولتی را نمی دهد: آنها اوتونوم خود مختار هستند. و در حالی که سونکارا درست میگوید که تحول اجتماعی "را می توان به صورت تجربی مورد بررسی قرار داد،" مقاله او- با تکیه بر منطق محدود توسعه گرایانه از تغییر آماری- دقیقا در .این مورد شکست خورده

.tatistical change—fails to do precisely that.

.tatistical change—fails to do precisely that.

EMANCIPATION!

رهائی

Take the following story, which is characteristic of the emancipatory social change that has been taking place in the Zapatista communities of Chiapas over the past 20 years; a story that is not visible in any official statistics.

A Basque friend I met in Chiapas a couple of years ago told me that what had impressed him the most during his last visit to the Zapatista communities was the position of women. The Basque comrade had come to Chiapas for the first time in 1996, two years after the uprising, and he could still vividly remember that women used to walk 100 meters behind their husbands, and whenever the husband would stop, they would stop as well to maintain their distance. Women would be exchanged for a cow or a corn field when they were married off—not always to the man of their choice. The situation has been very neatly depicted in the Zapatista movie Corazon del Tiempo.رنگ قرمز از منست

دوست باسکی* که من دوسال پیش در چیاپاس ملاقات کردم به من گفت که چیزی که او را در آخرین سفر خود به کومونیته های زاپاتیستها تحت تاثیر قرار داده است موقعیت زنان میباشد. رفیق باسکی برای اولین بار در سال 1996 به چیاپاس آمده بود ، دو سال پس از قیام ، و او هنوز به وضوح به یاد دارد که زنان بیش از 100 متر پشت سر همسران خود راه میرفتند، و هر زمان که شوهر می ایستاد ، آنها نیز توقف میگردند تا فاصله خود را حفظ کرده باشند. زنان را در وقت شوهر دادن با یک گاو و یا مزرعه ذرت تعویض/ رد و بدل میکردند- و نه همیشه با مرد مورد نهتخابشان . این وضعیت به بهترین وجهی در فیلم زاپاتیستا بنام دل زمانه به تصویر کشیده است .

*Basqueملتی که در منتهای شمالی اسپانیا زندگی میکنند و سالهاست که برای خود مختاری مبارزه و ( بمانند کردها) رزمنده و سلحشورند .

Women would be exchanged for a cow or a corn field when they were married off. Today, almost 20 years later, half of the EZLN’s commanders are women.

Almost 20 years later, my Basque friend returned to Chiapas for the first grade of the Escuelita Zapatista. This time he would freely dance with the promotoras after the events, while some of the highest-ranking EZLN commanders—or to be more precise for the lovers of statistics: 50 percent of the Commanders of the Clandestine Revolutionary Indigenous Committee—are actually women.

تقریبا 20 سال بعد، دوست باسک من به چیاپاس برگشت تا از کلاس اول زاپاتیستا دیدن کند. این بار او آزادانه با مروجین زن این کلاسها میرقصد، در حالی که برخی از بالاترین رتبه فرماندهان زاپاتیستا- و یا به عبارت دقیق تر برای دوستداران آمار: 50 درصد از فرماندهان بومی مخفی کمیته انقلابی را در واقع زنان تشکیل میدهند .

In addition, women are now forming their own cooperatives contributing to family and community income; they are becoming the promoters of education (teachers, that is), nurses and doctors; and they serve as members of the Good Government Councils, or Juntas de Buen Gobierno, and as guerrilleras.

علاوه بر این، زنان اکنون تعاونی های خود را تشکیل داده و به درآمد خانواده و کومونیته خود کمک میکنند؛ آنها مروجین آموزش و پرورش (یعنی، معلمان) میشوند، پرستاران و پزشکان؛ و آنها به عنوان اعضای شوراهای خوب دولتی در می آیند، یا هونتاس ده بوئن گوبیرنو (همان لقب به اسپانیائی-م) ، و بعنوان چریک نیز هم.

Let me give you another example that speaks for itself: In one of the Zapatista caracoles, there is now a music band called Otros Amores (“Other Loves”). Otros Amores is the phrase the Zapatistas use for the members of the LGBTQ community. All this in a previously deeply conservative, machista region (and country). Just try to imagine something similar in the rest of Mexico—or wherever you may be coming from!

اجازه بدهید یک مثال دیگر به شما ارائه دهم که بخودی خود نمایانگر میباشد: در یکی از که راکولس (حلزونها )ی زاپاتیستا ، در حال حاضر یک گروه موسیقی وجود دارد به نام اوتروس امورس ("عشقهای دیگر"). این عبارت را زاپاتیست برای اعضای کومونیته دگر سکس گرایان (هم سکس گرایان زن و مرد و ترانس...-م) استفاده میکنند. تمامی اینها در منطقه (و کشوری) که قبلا بغایت محافظه کار و ماچو/ مچیستا- مردسالار- بوده. فقط تصور کنید چیزی مشابه آن در بقیه مکزیک- یا از هر جائی که شما می آئید!

erever درyou m be coming from!

EDUCATION!

تعلیم و تربیت

At the same time, since the subject of education came up in Sunkara’s piece, it should be noted that—in an area where schools were an unknown word and teachers a very rare phenomenon—today there is not a single Zapatista community without a primary school, while secondary boarding schools now exist in the caracoles as well. This is a Zapatista achievement. These schools would not have existed without them.

همزمان، از آنجائی که موضوع آموزش و پرورش در مقاله سونکارا پیش آمد، باید توجه داشت که - در منطقه ای که در آن مدارس یک کلمه ناشناخته و معلمان پدیده بسیار نادری میباشند- امروز حتی یک کومونیته زاپاتیستها نیست که بدون یک مدرسه ابتدائی باشد، در حالی که مدارس شبانه روزی متوسطه نیز اکنون در حلزونها وجود دارد. این یک دستاورد زاپاتیستا است. این مدارس بدون آنها وجود نمی داشت .

Today there is not a single Zapatista community without a primary school. This is a Zapatista achievement.

Of course, the Zapatista autonomous rebel schools have nothing to do with the state schools: they are bilingual (Spanish and Tsotsil, Tojolabal, Tseltal, Chol, Mame or Zoque, depending on the region); they teach local indigenous history; and their syllabuses have been designed from the bottom up, with the active participation of the students and the communities, and are fully tailored to their specific needs.

البته، مدارس شورشی مستقل زاپاتیستا هیچ ربطی به مدارس دولتی ندارند : آنها دو زبانه هستند (اسپانیایی و سوتسیل ،توخولابال،سلتال، چول،مه مه یا زوکه ، بسته به منطقه)؛ آنها تاریخ بومی محلی را آموزش میدهند؛ و دروس درسیشان از پایین به بالا طراحی شده است، با مشارکت فعال دانش آموزن و کومونیته،و کاملا طراحی شده با نیازهای مشخصشان .

دا دانش آموزان و are fully tailored to their specific needs.

دا دانش آموزان و are fully tailored to their specific needs.

PARTICIPATION!

مشارکت کردن

Participation is a key concept when it comes to the social transformations that have been taking place in the Zapatista communities over the past twenty years. We are talking about deeply impoverished regions, where large estate owners used to rule over land and people, with the governors and the army of the—generally absent—federal state on their side.

مشارکت یک مفهوم کلیدیست وقتی که از تحولات اجتماعی که در بیست سال گذشته در کومونیته های زاپاتیستا اتفاق افتاده صحبت میکنیم. ما از مناطق عمیقا فقیر صحبت میکنیم، که در آن صاحبان املاک بزرگ قبلا بر سرزمین و مردم حکومت میکردند، با فرمانداران و ارتش - به طور کلی غایب- در کنار خود.

Participation is a key concept when it comes to the social transformations that have been taking place in the Zapatista communities over the past twenty years.

The relationship between the “bosses” and the “workers” was a rather slavish, almost feudal one, in which the bosses even had the right to the “first night” of their peasants’ wives (the so-called derecho de pernada). Some say that large finqueros like Absalón Castellanos Dominguez fathered numerous children with the wives and daughters of the workers of their ranches.

رابطه بین "کارفرمایان" و "کارگران" عملا برده وار، تقریبا فئودالی بوده، که در آن حتی کارفرمایان حق "شب اول" را از زنان دهقانان داشتند (به اصطلاح حق آقا ) بود. برخی می گویند که زمینداران بزرگی چون آبسالون کسته یه نوس دومینگز پدر کودکان متعددی از همسران و دختران کارگران مزارع خود بوده .

When it came to the expression of their democratic rights (which had until the 1994 uprising been limited to participating in elections), their votes were regularly exchanged for some pesos, some food, or were simply subject to the will of their ranch owner. Not surprisingly, the PRI was receiving over 90 percent of the vote in these lands.

هنگامی که صحبت از بیان حقوق دموکراتیکشان میشد (که تا قیام 1994 به شرکت در انتخابات محدود شده بود) ، رای شان به طور منظم مبادله میشد با چندرقاز پزوس(واحد پول مکزیک -م) ، مقداری مواد غذایی، و یا به سادگی با اراده صاحب مزرعه خود . جای تعجب نیست، حزب پی آر آی(قدیمی ترین و فاسدترین حزب در مکزیک-م) بیش از 90 درصد آرا را در سرزمینهایشان دریافت میکرد.

Today, every time I enter the offices of one of the Good Government Councils, I see different faces, very diverse age- and occupation-wise, who rotate in the administrative council every one to eight weeks, depending on the zone and caracol. I have seen old campesinos, 16-year-old graduates of the Zapatista schools, and young mothers breastfeeding their babies. They are all sent there by their communities for a given period in order to act as delegates in the collective self-administration of their lands.

امروز، هر بار که من وارد دفاتر یکی از شوراهای دولت خوب میشوم، چهره های متفاوت میبینم، از سنین و مشاغل بسیار متنوع ، که در شورای اداری هرکدام از یک تا هشت هفته میچرخند، بسته به منطقه و حلزون. من دهقانان مسن دیده ام ، فارغ التحصیلان 16 ساله از مدارس زاپاتیستا ، و مادران جوانی که در حال شیر دادن به نوزادان خود هستند. همه آنها توسط کومونیته شان برای یک دوره معین فرستاده شده اند تا بلکه به عنوان نماینده در خود اداره کردن جمعی/کلکتیو اراضی خود مشارکت بعمل آورند .

In the communities themselves, regular assemblies are organized from the bottom up to discuss local concerns and movement-related affairs, and to decide horizontally and directly on the issues that affect their everyday life.

در خود کومونیته ها، بطور منظم مجامع- انجمنها از پایین به بالا سازماندهی میشوند تا بلکه به بحث پیرامون مسائل محلی و امور مربوط به جنبش بپردازند، و به صورت افقی و به طور مستقیم در مسائلی که زندگی روزمره شان را تحت تاثیر قرار میدهد تصمیم گیری میکنند.

lives.

COMMUNITY, MUNICIPALITY, ZONE

جامعه/کومونیه، شهرداری، منطقه

The Zapatista communities—contrary to the army, the EZLN—have a horizontal structure. A given number of communities form an autonomous municipality (municipio autonómo), and a given number of autonomous municipalities form a zone (zona). The “administrative center”, which is also the office of the governing council of every zone is the caracol—which means snail.

کومونیته های زاپاتیستا- بر خلاف ارتش، ارتش آزادیبخش ملی زاپاتیستا- یک ساختار افقی دارد. تعداد معینی از جوامع-کومونیته ها یک شهرداری مستقل (شهرداری اتونوم ) را تشکیل میدهند، و تعداد معینی از شهرداریهای مستقل تشکیل یک منطقه ( زونا ) میدهند. "مرکز اداری"، که در ضمن دفتر 'شورای حکومتی در هر منطقه میباشد را 'که ره کول مینامند - که به معنی حلزون است.

The caracol is a very important symbol in the indigenous worldview and everyday practice of the Mayas, since it has traditionally been used to call the community to an assembly or to inform and communicate with other communities. For that reason, the snail represents “the word” (la palabra).

حلزون نماد بسیار مهم در جهان بینی بومی و عملکرد روزمره مایاها میباشد، از آنجائیکه به طور سنتی استفاده شده برای فرا خواندن کومونیته به مجمع/انجمن و یا برای اطلاع رسانی و ارتباط با جوامع دیگر . به همین دلیل، حلزون نمایندگی میکند و معنای "کلمه" میدهد .

There are five zonas and five caracoles, each with varying numbers of communities and municipalities. The Zapatista communities that administratively belong to each caracol do not necessarily hail from the same ethnic group. For example, the zone of Los Altos (“the Highlands”) is mainly ethnically Tsotsil, although it also includes some Tseltal communities.

پنج منطقه و پنج حلزون وجود دارد، هر کدام با تعدادی از جوامع و شهرداریهای متفاوت . جوامع زاپاتیستا که از نظر اداری به هر حلزون تعلق دارد لزوما از یک گروه قومی نیستند . به عنوان مثال، منطقه لوس آلتوس ( "ارتفاعات") به طور عمده از قوم سوتسیل هستند، اگر چه شامل تعدادی از قوم سلتال نیز میباشد.

Decisions are taken at the community level, in assemblies, with the participation of everybody who has completed their twelfth year of age.

تصمیمات در سطح جامعه، در انجمن، با مشارکت هر کسی که 12 سالش کامل شده باشد گرفته میشود .

The decisions are taken at the community level, in assemblies that take place either at the school, at the basketball court, or at the church (yes, they exist) of the community, with the participation of everybody who has completed their twelfth year of age. Each and every member of the community has the right to express their opinion and to vote on every single issue discussed. Every community selects its own representatives to the municipality, and each municipality selects its own representatives to the zone, who will eventually rotate in the Good Government Council.

تصمیمات در سطح جامعه گرفته میشود، در مجامعی که یا در مدرسه، در زمین بسکتبال، و یا در کلیسای کومونیته(بله، آنها وجود دارند) گردهم آیند، با مشارکت هر کسی که 12 سالش تکمیل شده باشد. هر یک از اعضای جامعه حق بیان افکار خود و رای دادن بر روی هر موضوع مورد بحث را دارد. هر کومونیته نمایندگان خود را به شهرداری انتخاب میکند، و هر شهرداری نمایندگان خود را به منطقه، که در نهایت در شورای دولت خوب به چرخش در می آیند.

The Good Government

Council is responsible for all the issues that have to do with the self-governance of the areas and the communities that belong to it: justice, politics, administration of natural resources, education, health, and so on. The caracol is also the place where seminars and gatherings with national and international civil society are organized. It is, in other words, the “entry point” through which those interested can enter Zapatismo, as well as its voice to the outside world.

Council is responsible for all the issues that have to do with the self-governance of the areas and the communities that belong to it: justice, politics, administration of natural resources, education, health, and so on. The caracol is also the place where seminars and gatherings with national and international civil society are organized. It is, in other words, the “entry point” through which those interested can enter Zapatismo, as well as its voice to the outside world.

حکومت خوب

شورا مسئول تمام مسائلی که مربوط به

خودگردانی مناطق و کومونیته های که به آن تعلق دارد میباشد: عدالت، سیاست، مدیریت منابع طبیعی، آموزش و پرورش، بهداشت، و غیره. حلزون هم محلی ست که در آن سمینارها و گردهمایی ها با جامعه مدنی ملی و بین المللی سازمان میابد. حلزون، به عبارت دیگر، "نقطه ورود"یست که از طریق آن علاقه مندان میتوانند به زاپاتیسم پیوند خورند، همچنین صدایشان به جهان خارج میرسد.

خودگردانی مناطق و کومونیته های که به آن تعلق دارد میباشد: عدالت، سیاست، مدیریت منابع طبیعی، آموزش و پرورش، بهداشت، و غیره. حلزون هم محلی ست که در آن سمینارها و گردهمایی ها با جامعه مدنی ملی و بین المللی سازمان میابد. حلزون، به عبارت دیگر، "نقطه ورود"یست که از طریق آن علاقه مندان میتوانند به زاپاتیسم پیوند خورند، همچنین صدایشان به جهان خارج میرسد.

THE SEVEN PRINCIPLES

هفت پرنسیب / اصل

The seven principles that define Zapatista self-government are the following:

هفت اصلی که خودگردانی زاپاتیستا را توصیف میکند به شرح زیر میباشند:

- To obey and not to command.

- اطاعت کردن و فرمان ندادن.

- To represent and not to supplant.

- نماینده شدن و نه جایگزین کردن .

- To move down and not upwards (in the sense of denying power-over).

- حرکت به پایین و نه به سمت بالا (به معنای انکار قدرت بر کسی).

- To serve and not to be served.

- خدمت کردن و نه بدست آوردن خدمات

- To construct and not to destroy.

- ساختن و نه داغان کردن

- To suggest and not to impose.

- پیشنهاد کردن و نه تحمیل نمودن

- To convince and not to conquer.

- متقاعد کردن و نه تسخیر نمودن

To avoid the professionalization of politics and the formation of leading oligarchies, each and every member of each and every Zapatista community has the right and the obligation to represent his or her community in the region and the zone once, for a very specific time period.

برای جلوگیری از حرفه ای شدن سیاست و تشکیل الیگارشی الیت گرا ، هر فرد و عضو هر جامعه زاپاتیستا حق و تعهد دارد تا یک بار به نمایندگی جامعه خود در منطقه ، برای یک دوره زمانی خاص برگزیده شود.

Once his or her mandate is over, he or she cannot assume the same right and responsibility again until all the turnos have been completed: until all the members of the community have been through that role.

هنگامی که دوره حکم او(چه مرد و چه زن) تمام میشود، او نمی تواند همان حق و مسئولیت را بعهده بگیرد تا اینکه همه نوبتها کامل شده باشند: تا زمانی که همه اعضای جامعه آن نقش را بعهده گرفته باشند.

The mandate of each Good Government Council varies from zone to zone and is set by the communities themselves. So, just to give an example, in the caracol of Oventik the council rotates every eight days, whereas in the caracol of La Realidad it does so every two weeks and in the caracol of Roberto Barrios every two months.

All the above is a product of the

همه مسائل فوق الذکر محصول جنبش

Zapatista movement, and would

زاپاتیستاست، و وجود نمیداشتند اگر

not have existed if the movement

جنبش ساختار سازمانی چپ سنتی را

had opted for a more traditionally

برگزیده بود .

leftist organizing structure.

OPENING UP NEW PATHWAYSباز کردن مسیرهای جدید

The only thing we proposed was to change the world. The rest we have improvised.

تنها چیزی که ما مطرح کردیم تغییر دادن جهان بود. بقیه اش بداهه سرائی بوده .

— Subcomandante Insurgente Marcosکوماندوی شورشی مارکوس

What is probably the greatest contribution of the Zapatistas to the international left—apart from reminding us that History had not truly ended just yet—is the fact that they managed to go beyond the usual recipes of the revolutionary cookbooks, re-inventing revolution with a “small r” and opening up innovative and autonomous pathways of democratic self-government. Of course, the Zapatistas did not start out that way.

چیزی که احتمالا بیشترین دستاورد زاپاتیستا به چپ بین الملل هست- جدا از یادآوری اینکه تاریخ هنوز حقیقتا به پایان نرسیده- این واقعیت است که آنها موفق شدند از دستور العمل های معمول کتابهای انقلابی فراتر روند ، اختراع دوباره انقلاب با لغت "آر کوچک"(به انگلیسی روولوشن-م) و باز کردن مسیرهای نوآورانه و مستقل برای خودگردانی دموکراتیک.البته، زاپاتیستا از اول اینگونه شروع نکردند.

The greatest contribution of the Zapatistas to the international left is the fact that they managed to go beyond the usual recipes of the revolutionary cookbooks.

What began as the armed wing of a Castro-Guevarrist, post-Tlatelolco revolutionary group did try—but eventually abandoned—the strategy of the foco guerrillero, and later switched to the Maoist prolonged people’s war. All of this did indeed bring about an attempt at the long-awaited Revolution with a capital R. However, when that Revolution failed as well after guerrilla groups elsewhere in Mexico failed to join the 1994 uprising, the Zapatistas actually had to open up new pathways. Through walking.

چیزی که به عنوان شاخه نظامی یک گروه انقلابی کاسترو- گواریست شروع شد ، گروه انقلابی پس از تلاتلولکو سعی کرد - اما در نهایت رهایش کرد-استراتژی فوکوی چریکی را ، و بعد به جنگ طولانی مدت مائوئیستی تغییرش داد. همه این در واقع تلاشی بود در انقلابی که مدتها انتظارش را میکشیدن با حرف آر بزرگ . حال آنکه، زمانی که آن انقلاب شکست خورد و همچنین گروه های دیگر چریکی در جاهای دیگر مکزیک به قیام 1994 نپیوستند، زاپاتیستا در واقع میبایست مسیرهای جدیدی را باز کنند . از طریق راه رفتن .

While they could have easily taken the beaten path of other armed revolutionary groups—going back to the jungle, that is, and keep attacking the army from there —they surprisingly opted for what has been called “armed non-violence” instead.

با این حال که آنها می توانستد به راحتی مسیر درب وداغان دیگر گروه های انقلابی مسلح را برگزینند- یعنی که، برگردن به جنگل، واز آنجا به ارتش حمله کنند - آنها با شگفتی آنچیزی را که "مسلح عدم خشونت" نامیده شده را انتخاب کردند.

The Zapatistas went back to their indigenous communities, consulted them, and decided to self-organize in an autonomous way. Without the Great Leaders, the all-powerful and all-controlling Parties, or the top-down vanguardist structures that the indigenous communities of Chiapas had already rejected a long time ago.

زاپاتیستا به جوامع بومی خود برگشتند، با آنها مشورت کردند، و تصمیم گرفتند که به سازماندهی خود به شیوه مستقل/اتونوم اقدام کنند. بدون رهبران بزرگ، احزاب بغایت قدرتمند و کنترل کننده، و یا با ساختار بالا به پایین پیشتاز که جوامع بومی چیاپاس مدت ها پیش آنرا رد کرده بودند.

“DON’T COPY US!”

از ما کپی نکنید

I had the opportunity to participate—together with hundreds of other activists—in the Escuelita Zapatista (the “little Zapatista school”) of August 2013. There, we spent time living and working together with several families of the Zapatista support bases in their own houses and communities, experiencing first-hand what freedom and autonomy according to the Zapatistas looks like.

من فرصت شرکت کردن، همراه با صدها نفر از دیگر فعالان - دراسکولیتا زاپاتیستا ("مدرسه کوچک زاپاتیستا ") را در ماه اوت2013 داشتم .در آنجا، ما وقت گذاشتیم زندگی و کار کردیم همراه با چند خانواده از پایگاه های پشتیبانی زاپاتیستا در خانه ها و جوامع/کومونیته هایشان، بشیوه دست اول آزادی و استقلال را بزعم زاپاتیستا تجربه کردیم.

The most important lesson of the Escuelita, however, was the farewell message to the students: a plea not to copy the organizational structure of the Zapatistas and their particular form of self-governance, but rather to rush back to their own lands and try “to do what you will decide to, in the way you decide to do it.” As they put it: “We cannot and we do not want to impose on you what to do. It is up to you to decide.”

مهمترین درس اسکولیتا/مدرسه ،هر چند، پیام خداحافظی به دانش آموزان بود: یک درخواست برای کپی نکردن ساختار سازمانی زاپاتیستا و فرم خاص خودمختاریشان، بلکه به سرزمین های خود برگشتن و سعی کردن " به کاری که شما تصمیم میگیرید ،با آن شیوه ای که شما تصمیم به انجامش میگیرید". آنطوری که میگفتند : " ما نمی توانیم و نمی خواهیم بشما تحمیل کنیم که چه باید بکنید. تصمیم گیری با شما ست . "

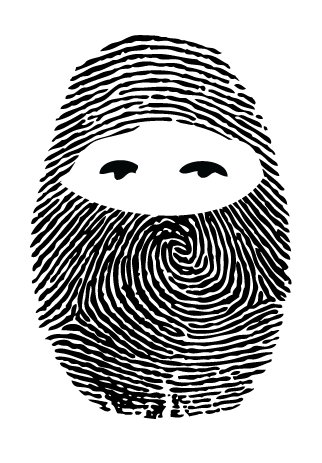

That was the humble message of

those proud and dignified people

who “cover their faces in order to

be seen, and die in order to live."

این پیام فروتن آن دسته از افراد مغرور و

با وقاری بود که "جهره هایشان را

میپوشانند تا بلکه دیده شوند، و

میمیرند تا بلکه زندگی کنند."

those proud and dignified people

who “cover their faces in order to

be seen, and die in order to live."

این پیام فروتن آن دسته از افراد مغرور و

با وقاری بود که "جهره هایشان را

میپوشانند تا بلکه دیده شوند، و

میمیرند تا بلکه زندگی کنند."

WHY WE STILL LOVE THE ZAPATISTAS

چرا ما هنوز عاشق زاپاتیستاها هستیم

Today, more than 20 years after the 1994 uprising, the Zapatistas are still there. Those previously illiterate, marginalized, exploited indigenous peoples of Chiapas are actually constructing a new world in the way they themselves have imagined it. Without revolutionary cookbooks and step-by-step theories of social change; without central committees, oligarchic Politbureaus or armchair intellectuals. Without hierarchies, revolutionary prophets or electoral politics—without too many resources either.

امروز، بیش از 20 سال پس از قیام 1994، زاپاتیستا هنوز آنجا هستند . کسانی که قبلا بی سواد بودند، به حاشیه رانده شده، مردم بومی استعمار شده چیاپاس در واقع در حال ساختن دنیای جدیدی هستند آنگونه که خودشان تصور کرده اند. بدون کتاب راهنمای انقلاب و نظریه های گام به گام تحول اجتماعی؛ بدون کمیته مرکزی، الیگارشی پولیتبورو یا روشنفکران صندلی نشین/کافی شاپ. بدون سلسله مراتب، پیامبران انقلابی یا سیاست انتخاباتی - و بدون هیچ امکانات زیادی .

The poorest of the poor, the most ignored of the ignored, have taught us a crucial lesson: that the construction of a new world is much more than an academic exercise. It is a matter of opening up new paths through walking.

فقیرترین فقرا، بیشترین نادیده گرفته شده از نادیده گرفته شدگان، به ما درس بسیار مهمی داده اند: که ساختن یک دنیای نوین خیلی بیشتر از یک تمرین دانشگاهی هست. موضوع باز کردن مسیرهای جدید از طریق پیاده روی(استعاره ای برای تلاشهای نوین و گزینشهای جدید-م) است .

That is what the international activists see in the Zapatista struggle, what they admire, and what they are inspired by. And of course, by rejecting the Party—in the traditional sense—as an organizational form, and representative democracy as a political system, they do not only “negate” in some kind of nihilistic approach.

That is what the international activists see in the Zapatista struggle, what they admire, and what they are inspired by. And of course, by rejecting the Party—in the traditional sense—as an organizational form, and representative democracy as a political system, they do not only “negate” in some kind of nihilistic approach.

این چیزی است که فعالان بین المللی در مبارزه زاپاتیستا می بینند، چیزی که تحسین میکنند، و الهام بخششان است. و البته، با رد حزب -در نوع سنتی اش-به عنوان یک شکل سازمانی، و دموکراسی نمایندگی به عنوان یک سیستم سیاسی، آنها آنرا تنها از نوع نیهیلیستی "نفی" نمیکنند .

They also create new, autonomous and direct democratic structures: from the piqueteros and the occupied factories of Argentina to the Coordinadora por la Defensa del Agua y la Vida in Bolivia; from the occupied squares and the social clinics, producers’ cooperatives and other bottom-up solidarity economy projects in Greece, Spain and Turkey, all the way to the polyethnic revolutionary cantons of Rojava—autonomous movements are building power everywhere.

آنها همچنین دست به ساختارهای جدید، مستقل و دموکراتیک مستقیم زده اند ومیزنند :(الهام گرفته-م) ازجنبش پیکه ته روز( کارگران بیکار- م) و کارخانه های اشغال شده آرژانتین بگیر تا جنبش هماهنگی برای دفاع از آب در بولیوی(علیه خصوصی سازی-م)؛ از میدانهای اشغالی و کلینیک های اجتماعی، تعاونیهای تولیدکنندگان و دیگر پروژه های اقتصاد همبستگی از پایین به بالا در یونان ، اسپانیا و ترکیه ، بگیر برو تا کانتونهای انقلابی جنبش روژاوا- جنبشهای مستقل/اوتونوم در همه جا در حال ساخت قدرتشان هستند .

“Asking we walk,” say the Zapatistas. And they do what they know best: to organize from below (and to the left), to imagine and create their own autonomous and democratic structures, and to be a shiny little light in the capitalist darkness. I personally see no harm in admiring them for that, and in trying to follow their example by imagining and creating similar structures, in our own lands, tailored to our own needs, shaped by our own dreams—without, of course, considering them to be yet another revolutionary recipe to copy.

زاپاتیستا ها میگویند "پرس و جو در حال راه رفتن" . و آنها آنچه را که خوب میدانند انجام می دهند : سازماندهی از پایین (و به سمت چپ)، با تصور کردن و ایجاد ساختارهای مستقل و دموکراتیک خود ، و نور براق کوچکی بودن در تاریکی سرمایه داری . من شخصا هیچ آسیبی در تحسین کردنشان در اینراه نمیبینم ، و در تلاش به دنبال نمونه خود با به تصور کشیدن و ایجاد ساختارهای مشابه، در سرزمین های خودمان ، متناسب با نیازهای خودمان، شکل داده شده توسط رویاهای خودمان -البته ، بدون، کپی کردن از آنها بعنوان یک دستور انقلابی دیگر.

No comments:

Post a Comment