20 Great Anarchist Movies That Are Worth

بیست فیلم آنارشیستی که ارزش وقت گذاری شما را دارند

Your Time

http://www.tasteofcinema.com/2015/20-great-anarchist-movies-that-are-worth-your-time/

There are hundreds, if not thousands, of films that address the themes of anarchism—some favorably (like most the films listed here) and some unfavorably. There are, as well, dozens of respected lists of “anarchist films.”

While almost every recent list of films and anarch thought lists V for Vendetta, one version or another of the story of Sacco and Vanzetti, and (disappointingly) either The Matrix or Avatar, this list eschews such titles. Rather, these are twenty films that in their anarchic form and/or content engage in “the conscious creation of situations,” to appropriate Guy Debord

.

The films raise more questions than they answer regarding leadership and decision making, hierarchies and egalitarianism, autonomy and heteronomy, equity and coercion, genre and storytelling, and intersections among race, class, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality. Such complexity, provocation, and affect make these films especially noteworthy.

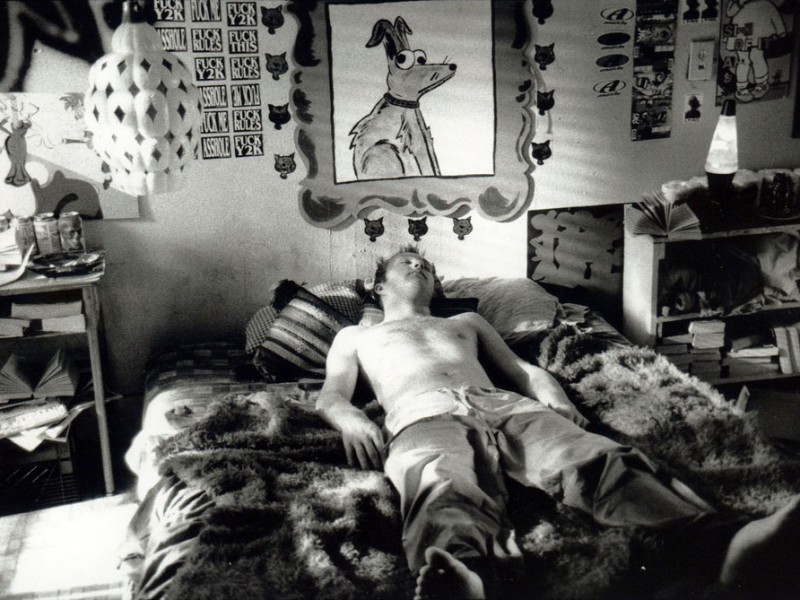

20. The Anarchist Cookbook (USA, 2002)

“We might not know what we’re for, but we know what we’re against.” Not so much an anarchist film as a hyper-individualist, chaos-driven narrative about a group of drop outs whose motto might be summed up as “Life is just a game,” The Anarchist Cookbook raises the issue of how to make films about anarchism without becoming cartoonish renderings of coercive cinema.

On the surface, this drama / romantic comedy is not about anarchist as much as it is about ill-conceived images of anarchists as counter cultural bufoons without focus.

More seriously, though, for our purposes here, a counter reading of the film calls into question mainstream images of anarchism and asks us to reconsider how the social tensions tweaked by such characters as Beavis and Butthead, Bill and Ted, and The Sweathogs might present more than meets the eye in terms of radical critiques of race, class, and social hierarchies.

19. What to Do in Case of Fire? (Germany, 2001)

Comedy about anarchism is difficult, in part, because comedy has to take its subject seriously. While What to do in Case of Fire takes on the interesting issue of what happens to young radicals years after they have settled into the system, it only half-manages to take its subject seriously enough to be comedic.

This film about former would-be revolutionaries accidentally pulled back into the fray is worth a look for the situation it describes and the few jokes it delivers. However, its reliance on sentiment and stereotype impede it developing authentic targets, such as are found in the best work of Chaplin and the Marx Brothers.

18. The Assassination of Trotsky (Italy/France/UK, 1972)

The Assassination of Trotsky was once voted one of the worst fifty films ever made, and in a 1972 New York Times review, Roger Greenspun referred to it as, “a very odd project indeed,” but one of director Joseph Losey’s which he preferred.

The film is a reenactment of the final months of Trotsky’s life beginning on May Day, 1940, in Mexico and is based on books, diaries, and journals about and by the Bolshevik-Leninist agitator and founder of the Red Army. Thus, it bears the weight of a certain history that is both heavily staged and cinematographically compelling.

17. Naked (UK, 1993)

Mike Leigh’s film is a controversial choice for this list. The rough story of Johnny (David Thewlis) escaping Manchester after he rapes a woman and is threatened by her family does not address community, direct action, or larger political movements against elite or coercive authorities. Yet, the film does provide a blunt critique of any “work ethic” and an assault on middle and working class morality.

After the opening crime, the anti-hero flees to London, where he avoids associating (let alone connecting) humanely with almost anyone and refuses to engage in work or constructive activity.

In sometimes lengthy speeches, he harangues those around him and accuses everyone of being bored and says that is the problem because he is never bored, never needs to be doing anything productive to pass the time. His special target is the women he encounters. The film remains ambiguous about the causes (political and/or social) behind Johnny’s anti-conformity and anti-humanist outlook, prompting viewers to consider him carefully.

16. The Anarchists (South Korea/China, 2000)

Directed by Yoo Young-sik and written by Lee Moo-young and Bangnidamae, The Anarchists is not as much an anarchist film as a film about the use of anarchism for nationalist aims. Set in 1920s Shanghai, the film recounts the activities of a group of young Koreans trying to destabilize Japanese control of their penninsula. Through an anti-occupation terrorist campaign, the five men hope to inspire a resurrection throughout their penninsular homeland.

The film addresses the ambivalence, violence, betrayal, and economic uncertainty that are themes in most such stories. Interestingly here, after “the anarchist” lose their financial backing, they turn to street crime and gambling.

Thus, the film raises issues about the connections between crime and terrorism not always broached in other cinematic depictions of direct political action and counter action. In its look and feel, The Anarchists deploys a mise-en-scéne similar to the one Ang Lee develops in his 2007 film about Chinese nationalist insurgency in Lust, Caution.

15. The Anarchist’s Wife (Germany/Spain/France, 2008)

Set during and after the Spanish Civil War and World War II, this film directed by Marie Noelle and Peter Sehr and written by Noelle and Ray Loriga is one of the few films addressing anarchism written, directed, and produced (Marie Noelle) by a woman.

It depicts the story of a woman and her family as they struggle to reconnect with her husband who fought against Franco’s forces, was caputured and deported to a concentration camp, and was unable to contact anyone for years.

The film is important for its engagement with personal and familial elements of anarchist and resistance warfare, for telling stories about the lives of those left behind—especially women and children. While The Anarchist’s Wife does portray its separate spheres in terms of a gendered binary—the man fights / the woman stays behind—it also takes the time to reconnect the “action” of the front to the “long-suffering” of the ones left behind the lines.

In this light, the film recalls especially Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s The Marriage of Maria Braun (1979), about a wife who is not allowed to connect with her husband until it is too late for either of them. Comparing the two films, one can begin to see a more subtle gender politics at play in both.

No comments:

Post a Comment