Imagining the End of Capitalism in

تصور پایان سرمایه داری در

‘Post-Occupy’ Dystopian Films: Part 2

فیلمهائی پیرامون ناکجا آباد 'پسا-اشغال' : قسمت 2

http://blindfieldjournal.com/2015/12/15/imagining-the-end-of-capitalism-in-post-occupy-dystopian-films-part-2/

By Madeline Lane-McKinley

“Utopia has been euclidean, it has been European, and it has been masculine. I am trying to suggest, in an evasive, distrustful, untrustworthy fashion, and as obscurely as I can, that our final loss of faith in that radiant sandcastle may enable our eyes to adjust to a dimmer light and in it perceive another kind of utopia. As this utopia would not be euclidean, European, or masculinist, my terms and images in speaking of it must be tentative and seem peculiar.” — Ursula K. Le Guin, “A Non-Euclidean View of California as a Cold Place To Be” (1982) [1]

The first part of this series focused on the populist fantasy of a ‘cinema of the 99%,’ as a staged encounter with recent dystopian films in Hollywood mass culture. Working against this fantasy, I began to suggest some ways to think about the dystopian turn of contemporary mainstream cinema in terms of broader historical tendencies of dystopia as a logic of capitalism. “The dystopian appearance is thus only the sharp edge inserted into the seamless Moebius strip of late capitalism,” as Fredric Jameson suggests, “the punctum or perceptual obsession that sees one thread, any thread, through its predictable end.” [2] In the present situation, dystopia is most useful to us when it is characterized, Jameson writes, “in terms of History, a History that we cannot imagine except as ending, and whose future seems to be nothing but a monotonous repetition of what is already here.” The problem posed by dystopia, in this sense, is how to locate radical difference — “how to jumpstart the sense of history so that it begins again to transmit feeble signals of time, of otherness, of change, of Utopia.” Rather than ascribe any particular novelty to the proliferation of dystopian culture over the past several years, I want to question this niche of post-Occupy films, and instead engage the dystopian structure of feeling as a historical tendency of capitalist crisis.

As a genre of crisis, dystopia has been historically conjured in periods of catastrophism. To this extent, dystopia is also a genre prone to reactionism. During the Cold War era, the dystopian imagination became primarily fixated on totalitarianism — as in Karl Popper’s conception of ‘utopia’ as inherently dystopian. [3] “The term utopia itself has been tarnished by association with totalitarianism,” as Lucy Sargisson suggests, partly because of “deliberate attempts to invalidate any proposed alternative to capitalism; anti-utopianism is a standard weapon in the armory of the status quo.” [4] In the post-Cold War era, totalitarianism is no longer the dominant modality of dystopian culture, although it remains a reliable trope in franchises like The Hunger Games. Instead, contemporary dystopias have taken a more apocalyptic orientation, often structured by a geo-imaginary of ecological crisis.

Whereas humanist and literary utopias began as cities and islands, dystopian novels especially proliferated after the shift toward temporal utopias — a shift which marked the complete eradication of a site beyond the horizon of western sea-power, through the course of the late eighteenth century. A number of recent dystopias return to this spatial trope of the island, and to the temporal register of an alternate present. What is remarkable about The Dark Knight Rises — as well as Cosmopolis— is the way in which the dystopian imagination is mobilized without the narrative suspension of a distant future. Instead, both of these films articulate a present for which the more predominant dystopian orientation toward ecological crisis is intrinsically linked to the actually existing dystopia of contemporary capitalism.

The “Anti-Occupy” Dystopia

ناکجا آباد "ضد جنبش اشغال": نقدی از دیوید گریبر و ژیژاک

ناکجا آباد "ضد جنبش اشغال": نقدی از دیوید گریبر و ژیژاک

Released in 2012, The Dark Knight Rises was critiqued by David Graeber as a “piece of anti-Occupy propaganda,” [5] and by Slavoj Zizek as “[tainting] OWS with the accusation that it harbors a terrorist or totalitarian potential.” [6] The film features a hostage takeover of the Stock Exchange, among other terrorist acts in an uprising led by Batman’s latest nemesis, Bane – who begins a “People’s Republic of Gotham City,” as Zizek insists, enclosing the island and exploding or barricading all surrounding bridges. Filmed in Manhattan contemporaneously with the encampment of Zuccotti Park, The Dark Knight Rises is the first of a series of referential films in the cultural moment of Occupy Wall Street. In the months following its release, many would take up the film as a provocation. Like Occupy itself, this provocation would bring together a contradictory sense of unity — a ‘cinema of the 99%’, formed from the false notion of an anti-Occupy blockbuster.

While Bane’s revolt in Gotham brings power to a world of criminals and freed prisoners, what is unknown within this ‘People’s Republic of Gotham City’ is that there is only a matter of months before a nuclear reactor will bring about total destruction. For Graeber, the central question is “why does Bane wish to lead the people in social revolution” in the first place? That this question is unanswerable within the narrative logics of the film only seems to suggest the ways in which its representation of Bane’s revolution comes with deep-rooted anxieties about a post-capitalist social order. Rather than pursue these anxieties as points of critique, however, Graeber seeks to articulate the film in terms of anti-Occupy propaganda. As Graeber argues, in the film, “something like Occupy could only have been the product of some tiny group of ingenious manipulators who really are pursuing some secret agenda.” Yet this critique is launched in defense of a populist vision that Graeber claims is strongly at work in the political moment of Occupy. Between the film and Graeber’s analysis, we find two dominant forms of reactionism, each of which describes the non-event of Occupy Wall Street.

Unlike Graeber, Zizek searches for a utopian dimension to Bane – “the source of his revolutionary hardness,” Zizek observes, “is unconditional love.” While recovering Bane from the fate of a villain, Zizek positions the character as “the mirror image of state terror, for a murderous fundamentalism that takes over and rules by fear, not for the overcoming of state power through popular self-organization.” In arguing that “the ongoing anti-capitalist protests are the opposite of Bane,” Zizek aligns entirely with Graeber’s conception of Occupy, while claiming that such “common-sense objections suggest themselves,” in an attempt to demystify the problem of violence at work in the mass media discourse of the social movement. In this sense, Zizek’s attention to Bane compels the following argument: “it is all too simplistic to claim that there is no violent potential in OWS and similar movements – there is violence at work in every authentic and emancipatory process.” Distinguishing between revolutionary violence and terrorism, Zizek claims that the rise of Bane in the narrative,

… changes things entirely. For all the characters, Batman included, morality is relativized and becomes a matter of convenience, something determined by circumstances. It’s open class warfare – everything is permitted in defense of the system when we are dealing not just with mad gangsters, but with a popular uprising.

Zizek’s defense of Bane bares its own set of symptoms – a particular urgency to re-tell the narrative against the reactionary politics of the Batman vigilante figure, who Graeber rightly describes as the ultimate right-wing superhero. And yet, in providing this critique of the film’s conception of revolution as terrorism, Zizek also states “the Occupy Wall Street movement in reality was not violent… Insofar as Bane’s revolt is supposed to extrapolate the immanent tendency of OWS, the film absurdly misrepresents its aims and strategies.” Ultimately, his reading of the film privileges the notion of a popular uprising – to the point of fascistically heroizing Bane as “the good terrorist.”

Both Graeber and Zizek critique The Dark Knight Rises on the basis of a populist imaginary of OWS, and it is precisely the way in which the film puts populism into crisis that remains under-theorized in both of their analyses. In contributing to this notion of OWS as a “popular uprising,” both readings reduce the utopian dimensions of the film and its capacity for post-capitalist imagination. While Zizek pieces together the utopianism of a dictatorship of the proletariat in Manhattan – the “event [which] is immanent to the film… its absent centre” – this interpretation marginalizes some of the more critical features of the film as a dystopia of the precariat. Zizek and Graeber both organize their analyses around the opposition between Batman and Bane, while neither accounts for the film’s conception of contemporary precarity.

As ‘Catwoman,’ Selina Kyle remains an unacknowledged counterpart to Bane and Batman – a figure of feminization and flexibilization, who vacillates between these oppositional poles in the narrative. She describes her mode of class antagonism to Wayne: “I take what I need to from those who have more than enough. I don’t stand on the shoulders of people with less.” Kyle opens a third reading of the film, to explore from her position within the revolution – her navigation between the film’s conception of anarchy, as Graeber describes, in the dynamic between “violence and creativity.” As Kyle threatens Wayne, “You and your friends better batten down the hatches, ‘cause when it hits you’re all going to wonder how you ever thought you could live so large and leave so little for the rest of us.” Kyle conveys a revolutionary element of the film, through forms of feminized and instrumentalized criminality rather than necessary or irrational violence, as figured in Batman and Bane.

Marginalized by the masculinist dichotomy of Batman and Bane, Catwoman makes use of her invisibility, and survives in Gotham through stealing and, implicitly, sex-work. Unlike Wayne, Kyle cannot compartmentalize her alter-ego – she lives in a world in which privacy no longer exists. In this sense, she is the ultimate flexibilized subject. Wayne, by contrast, contains Batman to his private fortress, acting at once as vigilante to the corrupt and incapacitated police state, and as savior philanthropist to dwindling institutions of social resources. As Kyle asks Wayne, “You think all this can last?”

While Zizek’s desire for a cinema of the proletariat – and indeed, for a correspondence between the ‘99%’ and proletarianism – fails to recognize the status of the precariat in the film, Graeber’s critique of The Dark Knight Rises’ anti-Occupy polemics would be more usefully examined as anti-utopianism. Nowhere is this anti-utopianism more apparent than when Wayne is captured by Bane, and placed in a remote prison, somewhere in North Africa, during the occupation of Gotham city. This is the prison from which Bane emerged – what he calls “hell on earth” — which encapsulates the film’s anti-utopian conception of the dystopian structure of feeling. At the bottom of a deep pit, the prison is most hellish because of its principle of hope: above the prisoners, the pit opens to a clear sky. “In here,” Bane explains to Wayne, “there can be no true despair without hope… as I terrorize Gotham, I will feed it hope.”

The dystopian genre, as Peter Fitting suggests, offers a critique of contemporary society that “implies (or asserts) the need for change,” whereas anti-utopianism “explicitly or implicitly [defends] the status quo.” [7] The Dark Knight Rises works out “the elision between perfection and impossibility,” as Ruth Levitas writes of anti-utopianism, which serves to “invalidate all attempts at change.” [8] Throughout the film, Wayne symbolizes the “necessarily modest and small-scale parameters of political reform” posed by what Kathi Weeks describes as the familiar logic of anti-utopianism. Such a logic conceives of utopian imagination as unrealistic “and therefore potentially dangerous distractions.” [9] Bane, in his illegibility as a revolutionary terrorist, comes to operate in terms of the film’s foreclosure of utopian imagination as post-capitalist possibility. In the end, the critical capacity of this urban dystopia — posed by Wayne’s reformist solutions to the privatization of Gotham — is reduced to a matter of charity from the elite class.

Of Dystopia and Capitalist Realism

از ناکجاآباد و واقع گرایی سرمایه داری

“Still, this is the advantage of the new direction, that we do not anticipate the world dogmatically but that we first try to discover the new world from a critique of the old one… If the construction and preparation of the future is not our business, then it is more certain what we do have to consummate — I mean the ruthless criticism of all that exists, ruthless also in the sense that criticism does not fear its results and even less so a struggle with the existing powers.” — Karl Marx, “Letter to Arnold Ruge”[10]

The unimaginability of a post-capitalist future is a structuring principle throughout this recent dystopian turn since the financial crisis. The indirectness with which such possibility exists in the imagination of these films must prompt a certain set of interpretive tactics. Whereas The Dark Knight Rises quite directly articulates a post-capitalist future in Bane’s self-described “necessary evil,” other films feature a more complicated struggle to dismantle this epistemological limit — presenting what Darko Suvin describes as “polemic nightmares.”[11]

Adapted from the French graphic novel Le Transperceneige, Bong Joon-ho’s Snowpiercer was released in South Korea in 2013, reaching the United States the next year. The film is his first to be predominantly in English. For the film’s speaking roles, Bong cast mostly actors from the US and UK – Tilda Swinton, Ed Harris, John Hurt, Octavia Spencer – and perhaps most notably Chris Evans, of Captain America fame, as Curtis, the film’s central anti-hero. Snowpiercer was immediately taken up as an allegory about the ‘99%’, begging the questions posed by Matthew Snyder’s reading: “What if Occupy Wall Street… had not only spread, but taken systemic root against the ruling class?”[12] Snyder describes the original graphic novel, by Jacques Lob and Jean-Marc Rochette, as “the occupy before occupy,” arguing that the novel’s concern “about resources, access, and social stratification are even more relevant to our times” than when it was first published in 1982. What is at stake in such a reading of the film? With the optics of a Hollywood blockbuster, Snowpiercer was absorbed into this vagary of a ‘cinema of the 99%’ – but it also puts forth a critique of such a phenomenon.

The film is a vision of the year 2031, which begins with a climate engineering scheme in 2014 – a last resort against global warming – that causes a global ice age which only a few survive on the ‘Snowpiercer,’ a massive train that travels across the frozen globe. As the opening sequence of the film explains:

SOON AFTER DISPERSING CW-7

THE WORLD FROZE

ALL LIFE BECAME EXTINCT

THE PRECIOUS FEW

WHO BOARDED THE RATTLING ARK

ARE HUMANITY’S LAST SURVIVORS

The train is organized as a class-based hierarchy, with the elite positioned in the front of the train, and a surplus population contained in the “tail section.” In this sense, the film extensively imagines global apocalypse, but in the form of a frozen class system — and one which, problematically, is organized by an outmoded metaphor. As a resistance to this notion of an ‘allegory of the 99%,’ the film is far more provocative when read in terms of the status of revolution in its dystopia. Like the sloganry of Occupy, class is reduced to hierarchism in the film’s metaphorical conjuring of the train, rather than a more complex system of exploitation and surplus. This fantasy of ‘class’ in frozen form seems symptomatic to a moment for which ‘class’ is a barely perceptible concept — a necessary pre-condition for the film’s revolutionary imagination.

Snowpiercer features two competing conceptions of revolution: the seizure or the destruction of the state. Throughout the film, this divergence is explored in two characters. While Curtis takes a teleological orientation – moving from the back to the front of the train, toward the seizure of its engine – Namgoong Minsu, the Korean specialist who engineered the security features of the train, continues to plot against Curtis’s revolt in order to escape. As they sit beside the gate to the engine car, Curtis tells Namgoong to open the gate, but Namgoong refuses: “You know what I really want? I want to open the gate, but not this gate. That one,” he explains, pointing to an exit hatch. As Namgoong argues, this hatch is “the gate to the outside world. It’s been frozen shut for 18 years. You might take it for a wall. But it’s a fucking gate.” While life on the train has been de-temporalized – epitomized in the currency of a drug called kronole – Namgoong has traced certain changes in the landscape, observing transformations in the outside world through the windows. Curtis, by contrast, hardly notices the windows. He is the realist – compelled by the ostensible necessity of the train, and convinced that there are no alternatives for survival. Namgoong is the idealist driven by the question, “What if we could survive outside?”

Curtis’s journey to the engine compels the plot, as Namgoong’s scheme to escape remains peripheral. Yet throughout the film, there is a central tension between these ideological constructs of the realist and idealist, through a sustained critique of the notion of impossibility. Although certainly adapting many of the tropes of post-apocalyptic dystopianism, the film resists the dystopian genre’s antinomies of possibility and impossibility. It is a persistently utopian film, which – in decentering the Captain America analog of Curtis – makes available a whole different set of interpretations through Namgoong. Near the end of the film, Curtis confesses to Namgoong that in his first months in the tail section, he had cannibalized other passengers:

… a thousand people in an iron box. No food and no water. After a month we ate the weak. You know what I hate about myself? I know what people taste like. I know that babies taste best. There was a woman. She was hiding with her baby and some men with knives came. They killed her and they took her baby. And then an old man of no relation – just an old man – stepped forward and he said ‘give me the knife.’ Everyone thought he’d kill the baby himself, but he took the knife and he cut off his own arm. And he said ‘eat this. If you’re so hungry, eat this. Just leave the baby.’ I had never seen anything like that. Me and the men put down their knives… and then one by one, other people in the tail section people started cutting off legs and arms and offering them. It was like a miracle. And I wanted to. I tried.

Once Curtis reveals that he was the man with the knife, the film begins to problematize his heroic realism – rendering him paralyzed by his sense of impossibility and desperation. Here, the film offers a compelling ideological critique of ‘human nature’ that is in keeping with radical elements of the utopian tradition. Crucially, this “miracle” exceeds Curtis’s realist expectations of what is entailed in survival in this most dire of situations. As the tail passengers begin to offer their own limbs, a collective possibility emerges – what eventually brings Curtis to the gate of the engine car in the film’s conclusion.

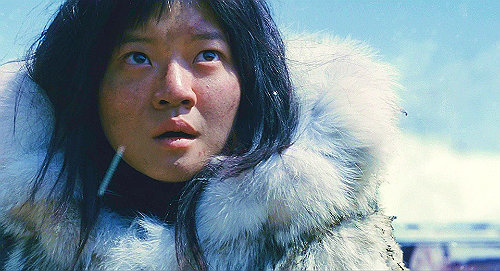

When Curtis finally makes it to the engine car, only to discover that a missing young boy from the tail section has been imprisoned to literally become a cog in the engine — compensating for a technical insufficiency — he comes to the realization that the train cannot be seized. If this is the condition by which the train must function, then the train should not function. Curtis decides to save Timmy, and they explode the train. Curtis and Timmy clutch onto Namgoong and his daughter, Yona, as the train decomposes, with cars exploding off the tracks and spreading across the snowscape. An inattentive and reductive reading of this scene — perhaps too caught up in the allegory that explodes with the train — presumes Yona and Timmy as the only survivors. While indeed Curtis and Namgoong are killed with the train’s destruction, the film includes a long sequence in which various train cars are scattered and in each contains the possibility of human survival. Yet the film’s conclusion lingers with indeterminacy, rather than providing forceful narrative closure – along the terms of its heavy-handed allegorization. Neither the idealist nor the realist position survives the explosion. It is at this point that the allegory no longer holds up – when Yona and Timmy emerge from the remains of the engine, to discover the tactile experience of life outside the train. Both “train babies,” Yona and Timmy figure a different set of possibilities from those imagined in the opposition between Curtis and Namgoong, whose deaths are hardly a plot-point of this closing sequence. As Yona and Timmy take their first steps in the snow, they hold hands and look out to an undiscovered country – a terrain of new possibilities, for which the terms of impossibility must be re-imagined.

While it is tempting to read this last scene as a sequence of impending failure, what is most remarkable about Snowpiercer’s conclusion is precisely its indeterminacy – the way in which it problematizes our own capacity to make their survival thinkable. The film is profoundly utopian, grounded in what Ernst Bloch distinguishes as an anticipatory rather than abstract utopia, designating “the truth and power of Marxism, which pushed the cloud in the dreams forward without extinguishing the fire of the dreams but rather strengthened them through concreteness.”[13] As opposed to a free-flow of non-meaning, the indeterminacy of the last scene provides this Blochian articulation of the utopian function as “the only transcending one that has remained, and [the only] one worth keeping,” of a “transcending [function] without transcendance.”

Snowpiercer can be engaged as a sustained critique of capitalist realism – what Mark Fisher describes as the “widespread sense that not only is capitalism the only viable political and economic system, but also that it is now impossible even to imagine a coherent alternative to it.”[14] For the critique of capitalist realism “to be of service to the present,” Alison Shonkwiler and Leigh Claire La Berge argue, it must make perceptible “the violence produced by a capitalism that constantly seeks to expand its sources and strategies of accumulation,” as well as the “lived economic, social, and affective instabilities of an entrepreneurial risk society,” while taking into account “how these are together transformed into a widely accepted brand of Gramscian ‘common sense,’ in which an inequitable, winner-take-all system of casino capitalism has seemingly achieved popular consent.”[15] In performing such a critique, Snowpiercerdismantles capitalist realism as a “longstanding tautology concerning rational expectations,” as Joshua Clover explains, which also describes the ideological tendencies of anti-utopianism. Positing a communist realism, Clover argues that:

The very idea of ‘rational expectation’ consigns any thought which cannot be recognized as having an instrumental expectation of gain to the realm of the irrational, the unrealistic. This ruling idea takes on even greater force in a crisis, when gain is ever harder to come by, and thus must govern ever more regions of thought and action, ever more rigidly.[16]

In its ultimate abandonment of Curtis’s realism, Snowpiercerseeks ruptures from this rational expectation precisely in response to crisis. While a meditation on the impossibility of a “coherent alternative,” as Fisher suggests, the film ultimately explodes from the containment of this binary opposition with the irrational and unrealistic in its final sequence. Yet in order to make such a critique imaginable, the film relies upon a static vision of contemporary class struggle, constructing its allegory of a global supply chain only through the demobilization and containment of these processes.

Whereas Snowpiercer ends with a vision of total destruction,Mad Max: Fury Road ultimately imagines the possibility of re-claiming the dystopian city from which its heroes initially fled. While Snowpiercer tends toward a more anti-civilizationist utopianism, Fury Road represents another recent dystopia that can be read as a critique of capitalist realism, which would be more effectively approached as an ideological interrogation of false scarcity than as another iteration of post-Occupy cinema.

The film begins with Max’s attempt to escape the Citadel, which is tyrannically governed by warlord Immortan Joe. Water and gasoline are scarce in this post-apocalyptic desert wasteland, but the Citadel consists of an elaborate infrastructure that Joe hoards for himself and his worshiping army of War Boys. In addition to agricultural production, the Citadel includes a vast social reproductive infrastructure, ranging from sex slaves to breast-feeders and blood-suppliers. After Max’s failed escape, the film follows Imperator Furiosa, who sabotages a mission to obtain resources from the nearby cities Gas Town and Bullet Farm, in an attempt to liberate five of Joe’s pregnant “wives.” Driving a large war tank, Furiosa stores the women as cargo, while they fight off Joe’s War Boys in pursuit of the “Green Land” – a matriarchy from which Furiosa was captured and brought to Joe’s citadel in her youth.

Much of the film involves an ornately choreographed chase, in which Furiosa becomes comrades with Max, and the wives become gradually more adept with guns. Furiosa, Max, a rehabilitated War Boy, and Joe’s wives eventually reach a collectivity of women in the desert, but they are told that the “Green Land” could not be maintained, and eventually turned into a swamp where nothing could grow. At first, Furiosa and the women part ways with Max, furthering their distance from the citadel. Max catches up to them, however, and persuades Furiosa – in a decidedly un-feminist scene, despite much of the film’s reception – that they should instead return to the citadel and assassinate Joe. When the surviving heroes return to the citadel with Joe’s corpse, they are celebrated by all of Joe’s former subjects. Max vanishes among the masses, while the women are raised on a lift up to the top of the citadel.

As in the dynamic between Curtis and Namgoong, we see between Max and Furiosa a dichotomy of realism and escapism. In either case, the utopian imagination is either racialized or gendered.

Fury Road is a fascinating critique of contemporary scarcity politics, for which the decisive moment is this turn back to the citadel. Not only is their return a critique of ‘impossibility,’ but an attempt to think through the already existing possibilities of post-capitalist social reproduction. Under Joe’s tyranny, the resources of the citadel have been privatized. Scarcity is rather an ideological construct – the premise of Joe’s power, and the condition by which Furiosa and Max diverge in their sense of possibility. While in Snowpiercer, the train’s dysfunctionality is conceived as unsalvageable, Joe is the site of dysfunction in Fury Road, kept alive with an elaborate respiratory machine and plastic-encased armor. In either case, the common sensical is uprooted, and it is capitalism that is made legible as irrationality.

From a marketing perspective, the feminist branding of this recent Mad Max is perhaps a point of curiosity, while it leads nowhere in terms of an analysis of its narrative. That the film cannot think outside the cultural imaginary of patriarchy reflects a more systemic problem of the contemporary imagination. As a vision of the abolition of private property, the consistentattempt of Fury Road is to imagine the breakdown of patriarchy. Within this narrative world, such possibility becomes activated by the desire for feminist collectivity. Counter-arguments citingFury Road’s failure to be feminist are also beside the point. It is more the film’s feminization of the dystopian genre that seems noteworthy – marking a critical juncture in this most recent dystopian turn of ‘post-Occupy’ cinema. Fury Road does not succeed at a total estrangement from patriarchy, but how could it? As in the notion of a ‘cinema of the 99%,’ our expectations of these films cannot go unchecked.

The mainstream feminist critiques of the film so far appear to focus mostly on the characters. Joe’s wives – the most nubile women of the citadel, we might presume – are anomalous to the post-apocalyptic landscape in their alignment with contemporary standards of beauty. Their fashion-model aesthetic contrasts with that of Furiosa, who takes on the appearance of a contemporary action hero instead. Whereas the film is incredibly imaginative in its orchestration of an elaborate and mobile terrain of struggle – from the citadel to the long journey on the “fury road” – it fails to incorporate women into its aesthetic world. As a dystopia, the film takes the structure of an analogy to the present, while the wives represent a point of contradiction. Everyone else in the film is dirty, and most of them will snack on a live desert lizard or beetle. Immortan Joe and his fellow warlords are both animalistic and crippled by nuclear catastrophe, the products of presumably generations of inbreeding, and his War Boys are hairless and painted in sand. The wives are aesthetically preserved from this narrative logic, and are thus relatable rather than analogical. As characters in a film uncommitted to character development, however, the wives do feature an interesting transformation from their existence as “objects” and “property,” as they discuss explicitly and even didactically, to warriors who risk and lose their lives for the purpose of revolution.

While being uninterested in its own characters, Fury Road is also uninterested in its own allegory. Like Snowpiercer, the film demonstrates a waning of the allegorical function in the dystopian genre, instead developing an intensely spatialized imaginary of subjugation as an analogy to the present. Like the train, the road must be destroyed – or at least, decapacitated in its allegorical function. The road’s purpose of escape is reversed. The characters are driven by revolution over retreat.

The intricately conceptualized citadel, featuring the various enclaves of Joe’s caste system, makes intelligible a critique of patriarchy as part of a broader scheme of domination and privation. Joe’s wives and children live in a locked safe. In another locked safe, he and his adult son drink fresh breast milk among a dozen women strapped to vacuum pumped suction machines. The film spatially elaborates this vision of post-apocalypse as a world of false scarcity. Outside the citadel, Joe’s impoverished subjects surround a large water spout that opens at the tyrant’s mercy onto a glaring, desiccated landscape. Within the citadel, the locked enclaves of Joe’s caste system are envisioned as a hierarchy in the vertical organization of the structure. Class division is made perceptible, predominantly through the saturation of hues – measuring the distribution of water throughout the citadel. Joe’s wives and children are bright, clean and hydrated, surrounded by a vibrant and lush color scheme. Through this contrast between the exterior and interior, the citadel shifts from the site of a dystopian order to that of a false utopia.

In its conception of the polis, Fury Road provides insight into the limits of the cultural imagination of the movement of squares. “[Besides] chasing a few ageing dictators down from their protests,” as Endnotes has argued, this movements of squares “achieved no lasting victories. Like the 2008-10 wave of protests, this new form of struggle proved unable to change the form of crisis management – let alone to challenge the dominant social order.”[16] This is the possibility haunting the final sequence of Fury Road. With Max disappearing into the masses, the film’s matriarchal uprising is an approximation of post-patriarchal power – indeed an attempt to imagine beyond the social relations of private property – while reproducing a hierarchy of sexual difference, a vision not premised on the abolition of gender, but on the re-structuring of gendered labor, as well as a political center.

As in Snowpiercer, Fury Road illustrates the limit-points of utopian imagination in contemporary culture, while drawing from ‘dystopia’ as primarily a mode of critique and intervention. This is distinct from the anti-utopian tendencies of The Dark Knight series, as well as franchises like The Hunger Games andDivergent, which extensively re-mobilize historical tropes of totalitarianism as a way out of the present — rather than a direct interrogation of contemporary fascism. Snowpiercer and Fury Road take up utopian problems more than solutions. These films, though not unproblematic, are unrelenting in their conception of the present as crisis. Rather than anti-utopia, their question is revolution.

*************************

Works Cited

[1] Le Guin, Ursula K. “A Non-Euclidean View of California as a Cold Place To Be,” Dancing at the Edge of the World: Thoughts on Words, Women, Places. New York: Grove Press, 1989. Print. 88

[2] Jameson, Fredric. “Future City,” New Left Review 21, May-June 2003

[3] Popper, Karl. The Open Society and Its Enemies. London: Routledge, 2002. Print. 78

[4] Sargisson, Lucy. “Utopia in Dark Times: Optimism/Pessimism and Utopia/Dystopia,” Dark Horizons: Science Fiction and the Dystopian Imagination. ed. Raffaella Baccolini and Tom Moylan. London: Routledge, 2003. Print. 15

[5] Graeber, David. “Super Position,” The New Inquiry, October 8, 2012. Digital.

[6] Zizek, Slavoj. “The Politics of Batman,” The New Statesman, August 2012

[7] Fitting, Peter. “Utopia, dystopia and science fiction”, The Cambridge Companion to Utopian Literature. ed. Gregory Claeys. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. Print. 137

[8] Levitas, Ruth. The Concept of Utopia. Oxford: Peter Lang, 2010. Print. 3

[9] Weeks, Kathi. The Problem with Work: Feminism, Marxism, Antiwork Politics, and Postwork Imaginaries. Durham: Duke University Press, 2011. Print. 175

[10] Marx, Karl. Karl Marx: Selected Writings. ed. David McLellan. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. Print. 43

[11] Suvin, Darko. “Theses on Dystopia 2001,” Dark Horizons: Science Fiction and the Dystopian Imagination. ed. Raffaella Baccolini and Tom Moylan. London: Routledge, 2003. Print. 189

[12] Snyder, Matthew. “Snowpiercer: Speak, Memory, Occupy”, Los Angeles Review of Books, August 8th 2014. Digital.

[13] Bloch, Ernst. “Art and Utopia,” The Utopian Function in Art and Literature: Selected Essays. trans. Jack Zipes and Frank Mecklenberg. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1988. Print. 107

[14] Fisher, Mark. Capitalist Realism: Is there no alternative?Winchester: 0 Books, 2009. Print. 6

[15] Shonkwiler, Alison and Leigh Claire La Berge. “A Theory of Capitalist Realism,” Reading Capitalist Realism. ed. Alison Shonkwiler and Leigh Claire La Berge. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2014. Print. 6

[16] Clover, Joshua. “Communist Realism,” Reading Capitalist Realism. ed. Alison Shonkwiler and Leigh Claire La Berge. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2014. Print. 242

[17] Endnotes, “The Holding Pattern,” Endnotes 3: Race, Gender, and Other Misfortunes.

No comments:

Post a Comment