را که به دیگران برتر هستند ایجاد کنیم

Imagine a two-tiered society with elite citizens, genetically engineered to be smarter, healthier and to live longer, and an underclass of biologically run-of-the-mill humans. It sounds like the plot of a dystopian novel, but the world could be sleepwalking towards this scenario, according to one of Britain’s most celebrated writers.

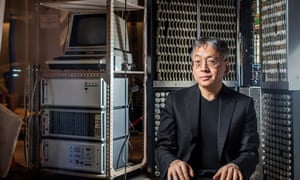

Kazuo Ishiguro argues that the social changes unleashed by gene editing technologies, such as Crispr, could undermine core human values.

“We’re going into a territory where a lot of the ways in which we have organised our societies will suddenly look a bit redundant,” he said. “In liberal democracies, we have this idea that human beings are basically equal in some very fundamental way. We’re coming close to the point where we can, objectively in some sense, create people who are superior to others.”

Ishiguro spoke to the Guardian ahead of the opening of a new permanent mathematics gallery at the Science Museum in London, which features a machine to predict coastal storm surges built by his oceanographer father, Shizuo Ishiguro.

The author hopes that the £5 million exhibition, and others like it, will encourage people to engage with the process of science and its future trajectory, rather than simply tuning in for the headline results of research and only then worrying about the implications.

“Despite the atom bomb and things like this, we’re still in the habit of compartmentalising scientific endeavour,” he said. “It’s important that we, as a society, get much more interested in science and maths, that we don’t silo it off in our minds ... until there’s some breakthrough product that turns up.”

Ishiguro cites three areas - gene editing, robotics and Artificial Intelligence - that he believes could transform the way we live and interact with each other over the next 30 years.

“We are on the brink of all kinds of discoveries that will completely alter the way we run our lives,” said the author, whose 2005 book, Never Let Me Go, imagines a dark future in which humans clones are raised to be organ donors.

The gene editing tool, Crispr, allows scientists to cut, paste and delete single letters of the genome with unprecedented precision, meaning aberrant genes can be overwritten with working copies, and, potentially, functional genes replaced with enhanced versions. Chinese scientists are already trialling the technology in patients to treat lung cancer.

“When you get to the point where you can say that person is actually intellectually or physically superior to another person because you have removed certain possibilities for that person getting ill… or because they’re enhanced in other ways, that has enormous implications for very basic values that we have,” said Ishiguro.

He also has concerns that in AI and robotics the bulk of intellectual capital lies with “the Silicon Valley masters of the universe” rather than universities or government-funded labs.

“There are some very powerful and rich people who want to do enormous research in this area,” he said. “Some of them might want to come out with things that are very beneficial, but it’s probably outside of regulation and so, yes, I think society as a whole needs to be more engaged.”

Ishiguro’s father, an oceanographer originally based in Nagasaki, moved with the family to Guildford, Surrey, to work at the National Institute of Oceanography in 1957, when Ishiguro was five.

Despite the two countries having been at war just a decade previously, the family were made welcome, he said. “The British people of that era had a very sophisticated sense of the international community because they had come through the war,” he said. “They knew the difference between serious things and less serious things, [having] lived through a period when they thought they were going to be under Nazi occupation.”

Ishiguro contrasts this with the anti-immigrant rhetoric that dominated the Brexit and US election campaigns.

“We have become much more multi-cultural and much more cosmopolitan in many ways, but the attitude to, say, the refugee crisis, I think is quite different to what I remember from the Britain I grew up in,” he said.

His father’s electronic analogue machine, which is the size of a large wardrobe, converted meteorological and ocean data (wind speed, tidal motion, water depth and so on) into electrical signals on a series of wire meshes. This allowed the height of storm surges, and where and when they would make coastal impact, to be predicted. The system was originally developed to help Japanese fishing fleets, but modified to be applied to the North Sea, where floods following a storm surge in 1953 led to more than 2,000 deaths.

Ultimately, the machine was superseded by digital computers, but the scientist continued to perfect his creation in the family garden shed in Guildford until his death in 2007 – a fact Ishiguro describes as “entirely unsurprising”.

Despite having taken a different career path, Ishiguro inherited an obsessive attitude towards work from his father, he said, recalling him mulling over equations every evening while watching American thrillers on television.

“Looking back now I can see that the whole approach to his work is quite like my approach to my work as a writer,” he said. “He didn’t think of it as a job at all. It was something he obsessively thought about the whole time. That was my model.”

No comments:

Post a Comment