http:// unsaidmagazine.wordpress.com

Alcoholism does not seem to be a search for pleasure, but a search for an effect which consists mainly in an extraordinary hardening of the present. One lives in two times, in two moments at once, but not at all in the Proustian manner. The other moment may refer to projects as much as to memories of sober life; it nevertheless exists in an entirely different and profoundly modified way, held fast inside the hardened present which surrounds it like a tender pimple surrounded by indurate flesh. In this soft center of the other moment, the alcoholic may identify himself with the objects of his love, or the objects of his “horror and compassion,” whereas the lived and willed hardness of the present moment permits him to hold reality at a distance. The alcoholic does not like this rigidity which overtakes him any less than the softness that it surrounds and conceals. One of the moments is inside the other, and the present is hardened and tetanized, to this extent, only in order to invest this soft point which is ready to burst. The two simultaneous moments are strangely organized: the alcoholic does not live at all in the imperfect or the future; the alcoholic has only a past perfect – albeit a very special one. In drunkenness, the alcoholic puts together an imaginary past, as if the softness of the past participle came to be combined with the hardness of the present auxiliary: I have-loved, I have-done, I have-seen. The conjunction of the two moments is expressed here, as much as the manner in which the alcoholic experiences one in the other, as one enjoys a manic omnipotence. Here the past perfect does not at all express a distance or a completion. The present moment belongs to the verb “to have,” whereas all being is “past” in the other simultaneous moment, the moment of participation and of the identification of the participle. But what a strange, almost unbearable tension there is here…this embrace, this manner in which the present surrounds, invests, and encloses the other moment.

The present has become a circle of crystal or of granite, formed about a soft core, a core of lava, of liquid or viscous glass. This tension, however, is unraveled for the sake of something else. For it behooves the past perfect to become an “I have-drunk.” The present moment is no longer that of the alcoholic effect, but that of the effect of the effect. The other moment now indifferently embraces the near past – the moment when I was drinking – the system of imaginary identifications concealed by this near past, and the real element of the more or less distanced sober past. In this way, the induration of the present has changed its meaning entirely. In its hardness, the present has lost its hold and faded. It no longer encloses anything; it rather distances every aspect of the other moment. We could say that the near past, as well as the past of identifications which is constituted in it, and finally the sober past which supplied the material, have all fled with outstretched wings.

We could say that all these are equally far off, maintained at a distance in the generalized expansion of this faded present, and in the new rigidity of this new present in an expanding desert. The past perfect of the first effect is replaced by the lone “I have-drunk” of the second, wherein the present auxiliary expresses only the infinite distance of every participle and every participation. The hardening of the present (I have) is now related to an effect of the flight of the past (drunk). Everything culminates in a “has been.” This effect of the flight of the past, this loss of the object in every sense and direction, constitutes the depressive aspect of alcoholism.

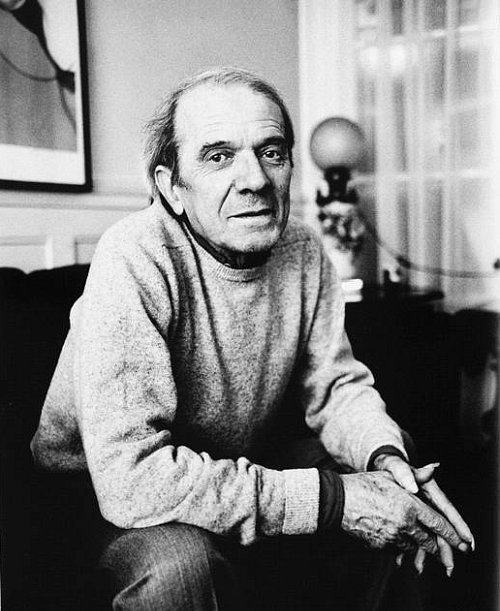

- Gilles Deleuze -

No comments:

Post a Comment